You have a million tokens of text. Your model’s context window is 128K. What do you do?

The common answers are RAG (chunk it, embed it, retrieve the relevant pieces) or long-context models (hope the window is big enough). But both have fundamental trade-offs: RAG loses global context because it only retrieves fragments, and long-context models degrade in quality as input length grows — the famous “lost in the middle” problem.

A recent paper from arXiv proposes a third approach: Recursive Language Models (RLM). The idea is deceptively simple — let the LLM program its own access to the document.

I built a working prototype. Here’s how.

What is a Recursive Language Model?

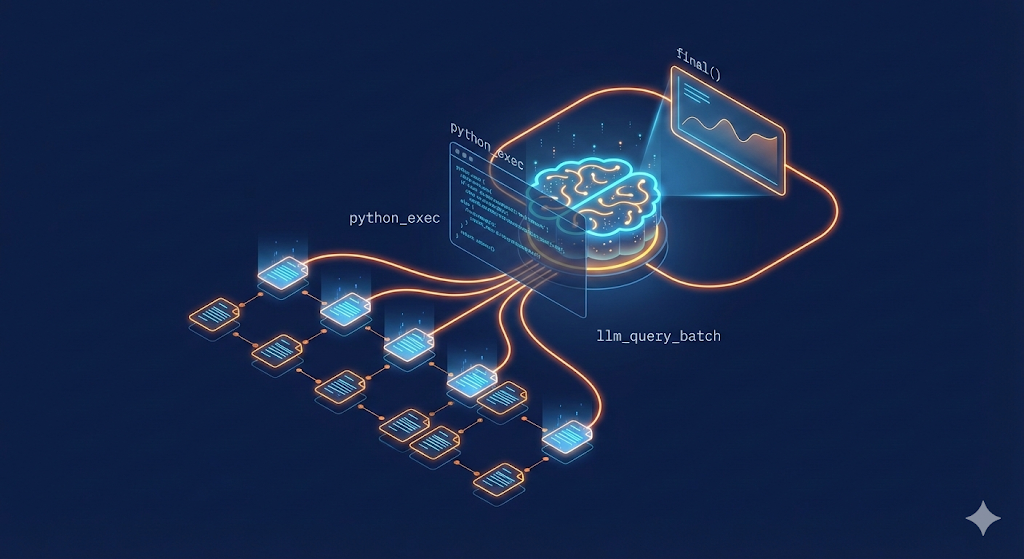

The RLM paper introduces an inference paradigm where the model treats a long document as an external environment rather than as input. Instead of stuffing the text into the prompt, the system:

- Loads the document into memory (a Python environment) where the model can’t see it directly

- Gives the model tools to examine, slice, and search the document via code execution

- Allows recursive sub-calls — the model can invoke itself on fragments to summarize or analyze them

This is fundamentally different from RAG. In RAG, a retrieval system decides what’s relevant before the model sees anything. In RLM, the model itself decides what to read, when, and how deeply — it writes Python code to navigate the text.

The key insight: LLMs are surprisingly good at writing code to explore data they can’t see. They search for patterns, slice around interesting regions, and use sub-calls to summarize sections — all autonomously.

The paper shows RLMs processing inputs up to two orders of magnitude beyond the context window, with ~28% performance gains over base models.

Architecture of the Prototype

The prototype has three components:

1. The Orchestrator

A turn-based loop that manages the conversation between the LLM and the Python environment:

for turn in range(1, max_turns + 1):

response = client.chat(

messages=messages,

tools=[python_exec, final],

tool_choice="auto",

)

# Process tool calls, collect observations

# Stop when model calls "final"The LLM has access to two tools:

python_exec(code): Execute Python code in a persistent environmentfinal(answer): Return the synthesized answer

2. The Persistent Python Environment

The full document is loaded as a string variable context in a Python environment that persists across turns. Built-in helpers:

context # The full document text (~4M chars)

context_len # Length

get_slice(start, end) # Extract a substring

search(pattern, max_results=5) # Regex search with context snippets

llm_query(prompt_text) # Sub-call to the LLM for fragment analysisThe critical one is llm_query(). When the model finds a relevant fragment, it can invoke a separate LLM call to summarize or analyze just that fragment — this is the recursive part.

3. The LLM API

Azure OpenAI with GPT-5 via tool calling. The system prompt tells the model it’s an RLM and that the document is NOT in its context:

You are an RLM (Recursive Language Model). The full document is NOT in your context.

The text is loaded in a Python environment as variable `context`.

Use python_exec to explore it with slicing and search.

Use llm_query() for sub-queries on fragments.

Call `final` with your answer when ready.Building the Demo: Step by Step

1. Setup

git clone https://github.com/JaviMaligno/rlm-prototipo

cd rlm-prototipo

uv venv && source .venv/bin/activate

uv pip install -e .

cp .env.example .env

# Fill in your Azure OpenAI credentials2. Collect Data (~1M tokens)

I wrote a script that downloads papers from arXiv and extracts clean text from LaTeX sources:

python scripts/fetch_arxiv.py --target-chars 4000000 --output-dir dataThis searches for papers on LLM agents, RAG, and AI — prioritizing LaTeX source extraction (cleanest text), falling back to PDF-to-text, and using abstracts as a last resort. It stops when it reaches the target character count.

In about 2 minutes, it downloaded 71 papers totaling 4,033,636 characters (~1M tokens).

3. Run the RLM

rlm run \

--input "data/*.txt" \

--question "What are the main contributions of these papers? \

Summarize the 5 most frequent themes."

# Defaults: --max-turns 15 --max-subcalls 90What Happens During Execution

Watching the RLM work is fascinating. Here’s the actual behavior on our 71-paper corpus:

Turn 1: The model checks the document size, identifies the structure, and samples representative fragments:

L = len(context) # → 4,044,992

starts = [0, L//3, 2*L//3] # Sample 3 positions

for st in starts:

frag = context[st:st+6000]

topics = llm_query(f"Extract 4-6 key topics:\n{frag}")Turn 2: With the initial themes collected, it synthesizes a final answer:

synth = llm_query(f"From these partial lists, identify the 3 main themes:\n{joined}")With a small budget (15 subcalls), the model completes in 2 turns, under 1 minute — sampling strategically and producing a coherent synthesis without ever seeing the full 1M tokens.

With a full budget (90 subcalls), the model analyzes all 71 papers individually in ~23 minutes, producing a detailed synthesis that cites specific paper titles, methods, and metrics. It used 80 subcalls for analysis and the rest for synthesis — all at 100% success rate.

Budget Management: The Key Design Decision

The most interesting engineering challenge wasn’t the architecture — it was resource management. When the model has limited subcalls across multiple turns, how should it allocate them?

The Problem

With 71 papers but only 15 subcalls, the naive approach fails:

# BAD: The model tries to iterate over everything

for section in sections: # 71 sections

llm_query(section[:8000]) # Burns all subcalls on turn 1

# No subcalls left for synthesis!Budget Visibility: Teaching the Model to Self-Plan

The solution was injecting remaining budget info into every tool result:

[budget] subcalls remaining: 11/15 | turns remaining: 4/5This simple addition transforms model behavior. Instead of iterating exhaustively, the model learns to sample representative fragments and reserve subcalls for synthesis.

Benchmark: Global Budget vs Refill-Per-Turn

I tested two strategies with identical parameters (5 turns, 15 subcalls):

| Global Budget + Budget Info | Refill Per Turn | |

|---|---|---|

| Time | 3:56 | 1:31 (no answer) |

| Subcalls used | 9 | 2 |

| Result | 3 themes with explanations | ”Max turns reached” |

| Behavior | Sampled, fell back to keyword search when subcalls failed, synthesized | Spent 3 turns exploring without subcalls, then failed |

Global budget wins decisively. The refill-per-turn approach removes urgency — the model “wanders” exploring without committing to subcalls. With a global budget and visible remaining count, the model plans its strategy around the available resources.

The global-budget model also showed better adaptability: when llm_query() calls returned empty (a GPT-5 issue), it autonomously fell back to keyword counting with search() — no subcalls needed.

Results and Lessons Learned

What Worked

The RLM successfully analyzed 71 papers and identified coherent themes across multiple runs:

- Security, ethics, and robustness — alignment, bias mitigation, adversarial resistance

- LLMs and NLP at scale — Transformer improvements, prompting, long-context reasoning

- Cross-domain AI applications — health, robotics, code generation, multimodal systems

GPT-5 Compatibility Issues

Building against GPT-5 required several fixes:

max_completion_tokensinstead ofmax_tokens(API parameter rename)- No custom

temperature— GPT-5 only supports the default value (1) - Tool call serialization — SDK objects needed explicit conversion to dicts for the message history

tools=nullrejection — GPT-5 returns empty content whentoolsandtool_choiceare explicitly set to null; these params must be omitted entirely

The Reasoning Tokens Trap

This was the hardest bug to diagnose. Sub-calls were returning content: null 100% of the time. The API wasn’t down — it was responding with finish_reason: "length" and consuming all tokens internally.

GPT-5 is a reasoning model (like o1/o3). The max_completion_tokens parameter includes both internal reasoning tokens and the visible output. With max_completion_tokens=800, the model would spend all 800 tokens “thinking” and have zero left for the actual response:

finish_reason: length

content: ""

reasoning_tokens: 800 ← all budget consumed here

completion_tokens: 800 ← nothing left for visible outputThe fix was increasing max_completion_tokens from 800 to 8000 for sub-calls. This gives the model ~2000-3000 tokens for reasoning and leaves plenty for the visible response (~500-1000 chars).

The result was dramatic: sub-call success rate went from ~6% to 100% (80/80 in our test run). What we had attributed to “intermittent API issues” was actually a systematic resource starvation problem.

Guardrails That Matter

Three guardrails prevented the most common failure modes:

-

Code length limit (50 lines max): Without this, the model writes enormous regex parsers instead of using

llm_query(). When rejected, it falls back to simple, correct code. -

Targeted error hints: Instead of a generic “error occurred”, the system provides specific guidance:

SyntaxError→ “Simplify your code. Use llm_query() instead of complex parsing.”Max subcalls reached→ “Synthesize with the data you already have and call final.”

-

Budget injection: The remaining subcalls/turns shown after each

python_execresult changed model behavior from “iterate everything” to “sample strategically”.

Self-Correction in the Wild

One of the most interesting emergent behaviors: the model writes buggy code, gets an error, and fixes it autonomously. Here’s a real example:

# Turn 3: Model tries to slice a dict like a list

KeyError: slice(None, 120, None)

# Turn 4: Model sees the traceback, realizes its mistake,

# rewrites the code using list indexing insteadThe model also self-corrects at a higher level. In one run, it found only 5 file separators instead of 71 because it searched for the wrong pattern. After seeing the unexpected count in the output, it tried a different approach and found all files.

This is not a bug — it’s the system working as designed. The agentic loop feeds every error back to the model as an observation, and the model learns from it within the same run. The guardrails (code length limit, error hints, budget visibility) keep these self-correction cycles short and productive.

Real-Time Output Streaming

A subtle but critical fix: the Python environment uses redirect_stdout during code execution, which captures all output — including the orchestrator’s progress logs for subcalls. The fix was pinning Rich Console to the real sys.stdout at construction time:

# Console(file=sys.stdout) stores a direct reference to the real stdout.

# When redirect_stdout later changes sys.stdout to StringIO, the Console

# still writes to the original terminal.

self.console = Console(file=sys.stdout)Without this, users watching the terminal during long python_exec blocks would see nothing until the entire execution completes — poor UX for runs that take 5+ minutes.

Trade-offs

| Aspect | RLM | RAG | Long Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| Setup complexity | Low (no embeddings, no vector DB) | Medium-High | Low |

| Global context | High (model explores freely) | Low (retrieval decides) | High |

| Cost | High (multiple API calls per query) | Low per query | Medium |

| Latency | High (sequential turns + subcalls) | Low | Medium |

| Max document size | Unlimited (out-of-core) | Unlimited | Window-limited |

RLM shines when you need deep, exploratory analysis of massive documents where you don’t know in advance what’s relevant. RAG is better for known-pattern retrieval at scale. Long context works when the document fits.

When to Use RLM

Use RLM when:

- Your document exceeds the context window and you need global understanding

- You need the model to decide what to read (exploratory questions)

- You want transparency — you can see exactly what code the model writes

Don’t use RLM when:

- You have a simple retrieval pattern (use RAG)

- Latency matters more than depth (RLM is sequential)

- The document fits in context (just use long context)

Phase 2: From Prototype to Production

The first version worked, but it had clear inefficiencies: the model wasted 2-3 turns parsing document structure, sub-calls ran sequentially (~10-25s each), and the model had no pre-built knowledge of available files. Three targeted improvements changed this.

1. Structure Helpers

Instead of letting the model discover file boundaries by parsing ===== FILE: separators manually, we now pre-compute a file index at load time and expose structured helpers:

file_count # → 71

list_files() # → [{index: 0, name: "paper1.txt", start: 0, end: 56234, size: 56200}, ...]

get_file(i) # → full text content of file iThis eliminates the exploration phase entirely. The model no longer needs to search("===== FILE:") and count separators — it knows exactly how many files exist and can read any one directly.

2. Injected Table of Contents

The first user message now includes an auto-generated TOC:

## Table of Contents (71 files, 4,044,992 chars)

[0] 2501.12345_paper_title.txt (56,200 chars)

[1] 2501.23456_another_paper.txt (48,100 chars)

...

[70] 2502.99999_last_paper.txt (61,300 chars)

Use `get_file(i)` to read file i. Use `list_files()` for details.Combined with the updated system prompt, the model’s recommended flow shifts from “explore → discover → sample → synthesize” to “read TOC → batch analyze → synthesize”.

3. Parallel Sub-calls

The biggest latency win. A new llm_query_batch() function runs multiple sub-calls concurrently using ThreadPoolExecutor:

# Before: sequential loop (~10s × 71 = ~12 min)

for i in range(file_count):

results.append(llm_query(f"Summarize:\n{get_file(i)[:6000]}"))

# After: parallel batch (~10s × 71 / 5 workers = ~3 min)

prompts = [f"Summarize:\n{get_file(i)[:6000]}" for i in range(file_count)]

results = llm_query_batch(prompts, max_workers=5)The implementation handles thread-safe subcall counting (via threading.Lock), pre-validates budget before starting, returns results in input order, and captures individual failures as [error: ...] strings without aborting the batch. If the batch exceeds the remaining budget, it processes as many prompts as fit and marks the rest as [skipped] — no wasted turns on errors.

4. The exec() Black Hole

An unexpected regression almost derailed Phase 2. Python’s exec() doesn’t auto-print expression return values — unlike an interactive REPL. With Phase 1’s multi-turn approach, the model accumulated results across turns so this didn’t matter. But Phase 2’s batch approach computes everything in a single python_exec: the model analyzed all 71 papers, synthesized them into a final_text variable… and got back stdout: 0 chars. The result vanished into nothing.

Worse, when the model then responded with plain text (it had the answer!), the guardrail nudged it back to python_exec — but with zero subcalls remaining, the model couldn’t use llm_query(), so it looped endlessly until max turns.

Two fixes:

-

Auto-capture last expression (like IPython):

PythonEnv.exec()now usesastto detect if the last statement is an expression, splits it from the body,eval()s it separately, and appends the result to stdout. The model no longer needs to know aboutprint()— it just works. -

Budget-aware nudge: When subcalls are exhausted and the model responds with text, the nudge now says “Call

final(answer=...)NOW with the data you have” instead of pushing back topython_exec.

5. Synthesis Truncation

Another subtle issue emerged: the model delegated synthesis to a llm_query() sub-call, passing all 71 file summaries (~42K chars) as the prompt. But sub-calls have a 6K character limit to keep costs down — so the synthesis only saw files [0]-[7] and cited nothing beyond that.

The fix: tell the model to synthesize locally in python_exec using the batch results already in memory, instead of delegating to another LLM call. The data is already there — no sub-call needed.

With these five improvements, the broad question went from 13 turns / 22:53 to 2 turns / 3:25 with full 71/71 coverage. But more problems remained.

6. Dual Strategy: Broad vs Specific Questions

Up to this point, the system prompt enforced a single strategy: “batch ALL files at once.” Great for broad questions (“summarize the 5 main themes”), wasteful for specific ones (“what vulnerabilities does the agent-fence paper identify?”). The model burned 71 subcalls scanning the entire corpus when it only needed one file.

The fix: two explicit flows in the system prompt:

- Flow A (broad question): batch all files, local synthesis,

final(). Unchanged. - Flow B (specific question): identify relevant files by name in the TOC, read FULL content with

get_file(i), split into ~30K-char chunks with overlap, and run focused subcalls to extract exact data.

We also raised max_subcall_prompt_chars from 6K to 32K — when the model needs to deeply analyze a full paper, it shouldn’t be truncating to 20% of the text.

7. Synthesis Nudge: The Exploratory Tourism Problem

Even with “don’t waste turns” written in the prompt, the model ignored it. After finishing its subcalls, instead of synthesizing and calling final(), it would launch round after round of search() and get_file() looking for “more data” until it exhausted all 15 turns.

The fix was structural, not verbal: a synthesis nudge mechanism in the orchestrator. After each turn with tool calls, the system compares the subcall counter with the previous turn’s count. If 3 consecutive turns pass without new subcalls (only python_exec with search() or reads), it injects a forced message:

“STOP. You have enough data. Synthesize what you have and call

final(answer=...)ON THE NEXT turn.”

This killed “exploratory tourism” at the root. The model now synthesizes immediately after the nudge.

8. max_tokens for Long Answers

The model sometimes said “the full message exceeds the limit, should I split it?” instead of calling final(). Root cause: max_tokens=4096 in the orchestrator’s main loop — long tool call arguments were being truncated. Raised to 16384 (matching the grace turn).

Before vs After (updated)

| Metric | Phase 1 | Phase 2 | Phase 2.5 (broad) | Phase 2.5 (specific) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Turns | 13 | 2 | 5 | 12 |

| Time | 22:53 | 3:25 | 4:13 | 3:22 |

| Subcalls | 80 | 71 | 71 | 8 |

| Coverage | ~50/71 | 71/71 | 71/71 | 1 paper in depth |

The broad question takes slightly longer than Phase 2’s best case (the model uses more turns to synthesize with 25K prompts instead of 6K), but summary quality is noticeably higher. The specific question is an entirely new use case: previously it was impossible to extract detailed data from a single paper without wasting the entire budget on the 71-file batch.

Video Demo

Run Logs

Flow A — broad question: "What is the main contribution? Summarize the 5 most frequent themes" (click to expand)

──────────────────── Turn 1/15 subcalls=0/90 elapsed=0:00 ────────────────────

LLM responded in 26.5s — content=False tool_calls=1

╭────────────────────────── python_exec (38L) 0:26 ───────────────────────────╮

│ files = list_files() │

│ prompts = [] │

│ for f in files: │

│ text = get_file(f['index']) │

│ chunk = text[:25000] │

│ prompts.append( │

│ "Summarize in 1-2 sentences the paper's main contribution..." │

│ + chunk │

│ ) │

│ results = llm_query_batch(prompts, max_workers=5) │

│ # ... classification by categories and local synthesis ... │

╰──────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────╯

⤷ llm_query_batch: 71 prompts, max_workers=5 (0:26)

⤷ llm_query #1/90 (0:26) 25219ch — Summarize the main contribution...

⤷ llm_query #2/90 (0:26) 25219ch — Summarize the main contribution...

...

⤷ llm_query #71/90 (3:05) 25219ch — Summarize the main contribution...

✓ 6.9s — 530 chars

✓ 8.9s — 548 chars

✓ 11.2s — 630 chars

✓ 25.8s — 720 chars

✓ batch done 182.9s — 71/71 succeeded

ok exec=182.9s stdout=13650ch stderr=0ch

╭──────────────────────── python_exec result (ok=True) ────────────────────────╮

│ {'summary': [('Evaluation and agent benchmarks', 25), │

│ ('Security, robustness and compliance', 19), │

│ ('Multi-agent coordination and reasoning', 13), │

│ ('Planning, memory and long-horizon tasks', 9), │

│ ('Scientific applications, health and specialized domains', 5)]} │

╰──────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────╯

[Turns 2-3: local synthesis with categories and concrete examples]

─────────────────── Turn 5/15 subcalls=71/90 elapsed=4:08 ────────────────────

2 text responses — accepting as final answer

╭──────────────────────────────── Final Answer ────────────────────────────────╮

│ Analyzed 71 papers. The 5 most frequent themes: │

│ - Evaluation and agent benchmarks (25 papers) │

│ • ScratchWorld: 83-task benchmark for multimodal GUI agents │

│ • PABU: progress-aware belief update, 81% success, −26.9% steps │

│ - Security, robustness and compliance (19 papers) │

│ • AutoElicit: elicits unsafe behaviors in computer-use agents │

│ • SCOUT-RAG: progressive traversal in Graph-RAG, reduces cost │

│ - Multi-agent coordination and reasoning (13 papers) │

│ • ICA: visual credit assignment via GRPO, beats baselines │

│ • RAPS: pub-sub coordination with Bayesian reputation │

│ - Planning, memory and long-horizon tasks (9 papers) │

│ - Scientific applications and health (5 papers) │

╰──────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────╯

Completed in 4:13 — 5 turns, 71 subcallsFlow B — specific question: "What vulnerabilities does the agent-fence paper identify?" (click to expand)

──────────────────── Turn 1/15 subcalls=0/90 elapsed=0:00 ────────────────────

╭──────────────────── python_exec (5L) 0:10 ─────────────────────╮

│ # Flow B: read the full file for the identified paper │

│ text = get_file(13) # ← agent-fence, identified via TOC │

│ len(text) # → 32037 chars │

╰─────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────╯

──────────────────── Turn 2/15 subcalls=0/90 elapsed=0:10 ────────────────────

╭────────────────────────── python_exec (13L) 0:18 ───────────────────────────╮

│ # Split into 20K chunks with overlap and launch batch │

│ chunks = [text[i:i+25000] for i in range(0, len(text), 20000)] │

│ prompts = [ │

│ "Extract the 14 attack types defined in Agent-Fence " │

│ "with exact names. Extract MSBR per architecture.\n" + c │

│ for c in chunks │

│ ] │

│ results = llm_query_batch(prompts) │

╰──────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────╯

⤷ llm_query_batch: 2 prompts, max_workers=5 (0:18)

⤷ llm_query #1/90 (0:18) 25384ch — Extract the 14 attack types...

⤷ llm_query #2/90 (0:18) 12421ch — Extract the 14 attack types...

✓ 26.0s — 223 chars

✓ 34.4s — 206 chars

✓ batch done 34.4s — 2/2 succeeded

──────────────────── Turn 4/15 subcalls=3/90 elapsed=1:05 ────────────────────

# Sends the full paper (32015ch) in a single subcall to confirm

⤷ llm_query #3/90 (1:05) 32015ch — Read the Agent-Fence paper and extract...

✓ 31.2s — 640 chars

╭──────────────────────── python_exec result (ok=True) ────────────────────────╮

│ 1) Attack types (exact names): │

│ 1. Denial-of-Wallet 2. Authorization Confusion │

│ 3. Retrieval Poisoning 4. Planning-Layer Manipulation │

│ 5. Tool-Use Hijacking 6. Objective Hijacking 7. Delegation Attacks │

│ 8. prompt/state injection 9. retrieval/search poisoning │

│ 10. delegation abuse 11. Unauthorized Tool Invocation (UTI) │

│ 12. Unsafe Tool Argument (UTA) 13. Wrong-Principal Action (WPA) │

│ 14. State/Objective Integrity Violation (SIV) │

│ │

│ 2) MSBR per architecture: │

│ - LangGraph: 0.29 ± 0.04 │

│ - AutoGPT: 0.51 ± 0.07 │

╰──────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────╯

[Turns 5-8: exploratory search() without new subcalls]

──────────────────── Turn 9/15 ────────────────────────────────────────────────

⚠ 3 turns without new subcalls — nudging to call final()

──────────────────── Turn 10/15 subcalls=8/90 elapsed=3:13 ──────────────────

# Synthesizes immediately after the nudge

╭─────────────────────── python_exec result (ok=True) ───────────────────────╮

│ Vulnerabilities and attack types (14 classes defined by Agent-Fence): │

│ 1. Denial-of-Wallet 2. Authorization Confusion │

│ 3. Retrieval Poisoning 4. Planning-Layer Manipulation │

│ 5. Delegation Attacks 6. Objective Hijacking 7. Tool-Use Hijacking │

│ 8. prompt/state injection 9. retrieval/search poisoning │

│ 10. delegation abuse 11. Unauthorized Tool Invocation (UTI) │

│ 12. Unsafe Tool Argument (UTA) 13. Wrong-Principal Action (WPA) │

│ 14. State/Objective Integrity Violation (SIV) │

│ │

│ MSBR per architecture: LangGraph 0.29±0.04 — AutoGPT 0.51±0.07 │

╰────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────╯

───────────────────────────────── Final Answer ─────────────────────────────────

Completed in 3:22 — 12 turns, 8 subcallsNote: the original paper cites 8 evaluated architectures, but the PDF-extracted text only contains explicit MSBR data for LangGraph and AutoGPT. The tables with all 8 architectures likely existed as images/LaTeX tables and didn’t survive the text conversion.

What’s Next

Remaining improvements for production readiness:

- Result caching across runs for repeated queries on the same corpus

- Cost tracking per query for production budgeting

The full source code is available at GitHub repository.

Based on the paper “Recursive Language Models”. Built with Azure OpenAI GPT-5 and Python.